(The Claridge | Photo: Al Shapiro)

In Philadelphia, discussions about affordable housing tend to assume a binary world with "affordable housing" on one side, and "market rate" housing on the other. "Affordable housing," as the term is commonly used, assumes some form of public subsidy is going to be required, while "market rate" housing is assumed to be too expensive for the average person to afford, just by definition.

Of course, all housing receives some type of public subsidy, whether it's the federal mortgage interest deduction, Philadelphia's 10-year tax abatement on property improvements, or sundry other federal, state, and local policies designed to promote homeownership. What people invoking "affordable housing" usually envision though is that it will involve some type of public spending, like tax credit financing, direct public construction, Section 8 rent vouchers, and so on. It's not just any dwelling that happens to have a modest price tag.

But this binary frame is mistaken, and it tilts the local policy response toward approaches like Darrell Clarke and PHA's misadventure in Sharswood, that are not only unaffordable and unsustainable for taxpayers, but also fail to produce anywhere close to the amount of housing that is needed.

With federal and state funding for tax credits and public construction already drying up under conservative regimes in Washington and Harrisburg, Philadelphia needs a totally different approach to affordability centered on abundant housing construction and redevelopment, and a larger range of housing choices.

It starts with the recognition that the vast majority of Philadelphians are not eligible for tax credit-financed or publicly-constructed housing. Most people are buying or renting housing at market rates, and city policy is currently doing nothing to make that part of the market more affordable for the average Philadelphian.

In fact, many elected officials will tell you their goal is just the opposite: to maintain strong home price growth for homeowners. Former 1st District Councilman Frank DiCicco (who Jim Kenney is reportedly considering to chair the powerful Zoning Board of Adjustment) bragged on WHYY last year that his big down-zoning of eastern South Philadelphia in his first term set the stage for today's home prices "going through the roof," which he thinks is a good thing.

"The remapping was to remove, as a matter of-right, conversion of single-family dwellings into multi-family. If anyone is familiar with South Philadelphia, South of Snyder in particular on the west side where people triple-park, and put their phone number on the dash...I didn't want to see that happen on the east side where I represented. There were developers, there were realtors who wanted to hang me by my toes. I was stopping development, I was creating hardships for them. Ultimately, in general I think we saved neighborhoods, protected as many of the single-family dwellings, and property values in that neighborhood are going through the roof."

New research from Enterprise Community Partners, summarized by Patrick Clark at Bloomberg, makes the case that DiCicco's understanding of the relationship between zoning and housing costs is basically right. Clearing out all the apartment zoning is a great way to make a neighborhood less affordable.

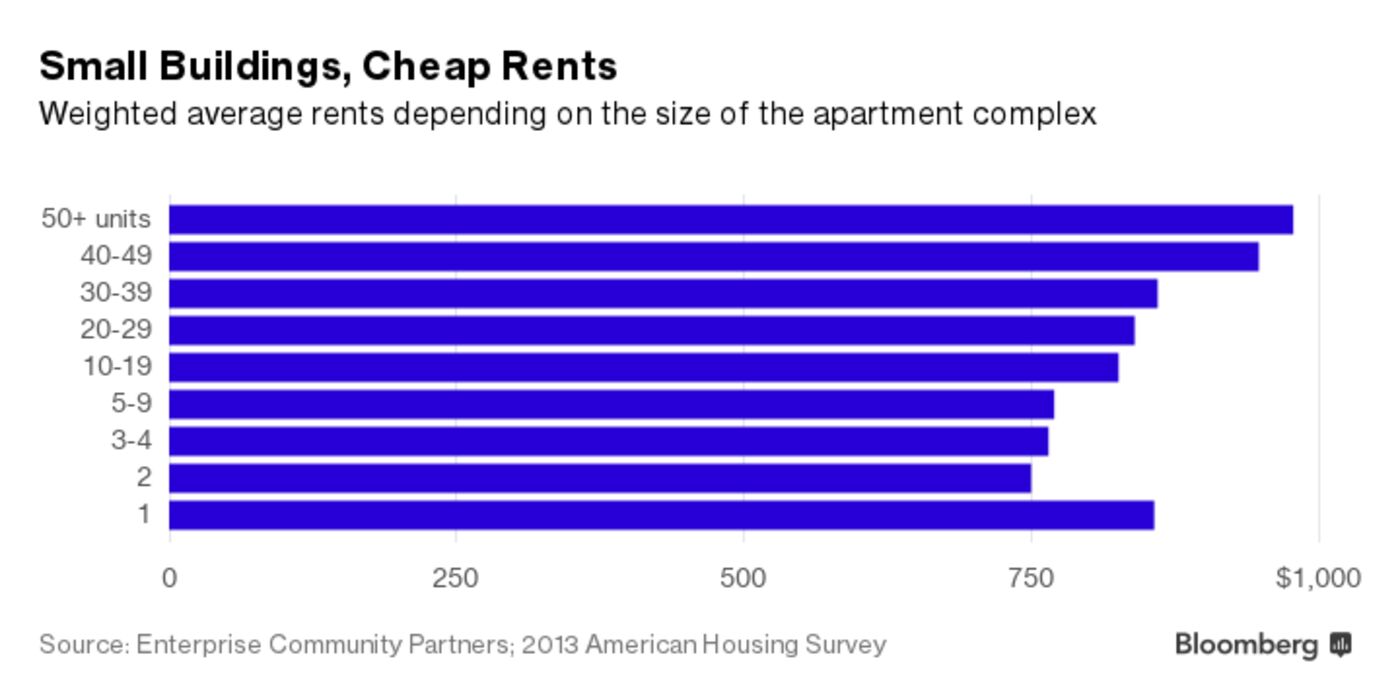

According to new research from Enterprise Community Partners, an affordable housing nonprofit, and the University of Southern California, apartment buildings with between two and nine units offer the lowest prices available to U.S. renters.

The chart above uses data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013 American Housing Survey to show average monthly rents based on the number of apartments in a building. The paper categorizes buildings with between two and 49 apartments as “small and medium multifamily housing”—a grouping that makes up 54 percent of the U.S. rental stock.

As noted, America isn’t building as much of this kind of housing as it used to. Small- and medium-size apartment complexes account for a quarter of existing units built in the 1970s and 1980s, according to the report. Since 1990, though, the category has accounted for just 15 percent of new housing stock.

This paper is about renters, but the same math applies to owner-occupied condos in multifamily buildings. Duplexes, triplexes, and smaller multi-unit buildings are lower-cost, because it's cheaper to split the land costs of a rowhouse-sized parcel among more households. Developers who are building in neighborhoods outside of Center City are keeping their asking prices affordable by building denser housing styles.

This report shows that rents in larger buildings are less affordable (starting at around 30-39 units), owing in part to the jump in construction costs associated with building a larger structure.

That means allowing more small and mid-size multifamily buildings to inter-mix with single-family dwellings in more neighborhoods would likely pack a greater punch in terms of affordability than the current policy of trying to fence the whole rental market into a small area in the heart of Center City.

In Philly, RM-1 (the zoning category for small apartment buildings) is very similar dimensionally to RSA-5 (single-family attached rowhouses), so there isn't an issue with RM-1 buildings towering over the rest of the block. The "context" objection doesn't really apply since the same 38' height limit applies.

The issue, as DiCicco says, is all about street parking and fuzzy objections to density and renters.

Those types of concerns need to be balanced against the City's rhetorical stance in support of keeping Philly affordable. For a long time, when the city was expected to keep declining in population every year, politicians could act like erasing all the apartment zoning in a neighborhood was a freebie. What did it matter if the City was going to keep shrinking anyway?

But now that the housing market is on fire, and Philadelphia continues to be revalued upward by regional and national home buyers, banishing unsubsidized affordable housing types like low and mid-rise apartment buildings, condo buildings, and triplexes is increasingly irresponsible and costly from an affordability perspective.

Elected officials have yet to really grapple with this, and neither has the Planning Commission. They aren't even tracking whether the total supply of developable space has been expanded or shrunk through all the various zoning remapping bills, so it's a mystery as to whether Philadelphia's housing market has become more or less capable of supplying all the housing that people want.

To stay in the loop on political news, events, and updates from Philadelphia 3.0, sign up for our email newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Be the first to comment

Sign in with

Facebook